I have a love-hate relationship with my local airline. In the past, I was a big fan of Cathay Pacific. They were slightly more expensive but the service and amenities were much better than the competition.

But over the past few years, the relationship has changed. Firstly, they changed their loyalty programme, making it much harder to achieve any frequent flyer status unless you are a corporate traveller willing to pay full fare economy/business. Secondly, even when I have flown with them, I find that they have pared back their services so much that I wonder if they are worth it. Now, I am packed in like the sardines above and the food offering leaves a lot to be desired. It reminds me a lot of when I used to fly on US domestic flights. The flights were always full and people brought their own food on board.

But here is where the love-hate part comes in. Just because I don’t like the service, does it mean I should also dislike the stock? After all, if the airline is now cutting costs and becoming more efficient, is that not good for shareholders? It is a fine line because if consumers have other choices, then top line revenue may fall faster than cost savings.

How the greats have fallen – CX market cap

If one were to look at how far the likes of Cathay Pacific and Singapore Airlines have fallen you only have to consider their market caps. At US$6bn, Cathay Pacific’s market capitalisation is now less than a quarter that of the three big American airlines. Its market cap is also less than half of the three Chinese airlines, 30% smaller than Singapore Airlines and 25% smaller than Qantas.

Challenges – Competition, fuel and small markets

Now, there are real challenges facing CX which help to explain why it has fallen so far behind its peers. There is the rising competition from the budget airlines. There is the fuel hedge that has gone horribly wrong and there is also the fact that it serves a much smaller market.

Fleet size and average age – CX at 9.0, SQ and CA at 6.4 yrs old

One stat where this shows up is fleet size. At the end of 2016, CX had a fleet size of 189 airplanes. SQ is slightly smaller at 178 planes but just to CX’s North, the three Chinese airlines have an average of 640 planes. The three US airlines is more than double that at 1,356 planes.

What’s interesting is the average age of the fleet. I kind of guessed that SQ’s fleet would be very young at 6.4 years old. With China’s strong growth and acquisitive nature, it was also not a surprised that their fleet was only 6.1 years old. But I was quite surprised to see that Cathay’s fleet is now 9.0 years old. By comparison, although the American airlines have much larger fleets, they are much older with an average age between 10.3 and 17.0 years.

As consumers, we would of course prefer the newer plane. From a business perspective, although the newer planes offer better fuel efficiency, they cost money, lots of money.

Here I would suggest that one reason why the US airlines have higher market cap and higher valuation is partly due to their older fleets. First, the lower depreciation charge help to boost operating margins. Second, on a cash flow level, the more conservative replacement strategy has meant that Operating Cash Flows tended to exceeded capital expenditure. In other words, they are earning more cash than they are spending on new planes. Notably, Air China and China Southern, despite building up a very young fleet have also managed to keep Operating CF above capex.

On the flipside, we see that SQ and CX have operating CF that are 0.64x and 0.41x that of capex. As we alluded to earlier, part of CX’s problem is due to a fuel hedge gone wrong. This cost CX approximately HK$8.5bn in 2016 and if one were to exclude this loss, CX’s operating CF to capex ratio would be around 0.98x but still below 1.0x.

What about competition from budget airlines?

Relative to the US, budget airlines have had a much shorter history in Asia. So, in order to gauge their potential impact, we look to the US to see how they may have affected revenue growth and margin.

At a glance, we can see that in 2016, the three US airlines saw revenues declining by 2.68% on average. While revenues declined, the US airlines enjoyed the highest operating margin of 14.2%. This is even higher than the Chinese airline’s average operating margin of 13.0%. So while competition from budget airlines could lead to an overall decline in top line revenue, this suggest that profitability could still be maintained with greater efficiency.

Load factors and costs management

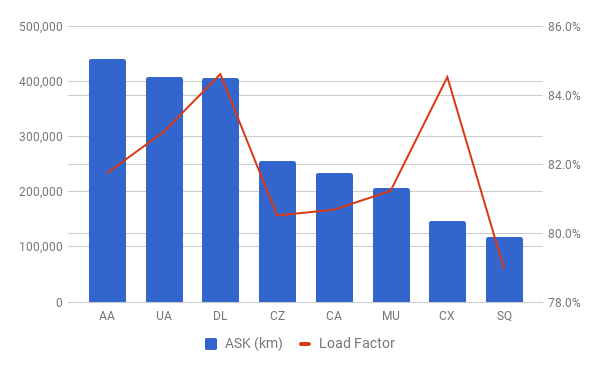

In order to dissect the efficiency issue further, we consider load factors. Is CX’s problem tied to too many empty seats or is it because its running costs are too high?

Load factor not the problem, CX packing them in like sardines

As the following chart shows, CX actually fills their flight as tightly as the US airlines do. In 2016, CX’s load factor (kind of like an occupancy rate) of 84.5% is only a little bit below Delta’s 84.6%. It is in fact higher than AA’s 81.7%, UA’s 82.9% and much higher than the Chinese airline’s 80.8% load factor.

If CX’s problem is not too many empty seats, are the budget airlines causing it to sell its seats too cheaply? This might be the case. When we divide total revenues by total passengers kilometres flown, we see that CX earned an average of 9.7 US cents per kilometre. Interestingly, despite the competition from budget airlines, the US airlines commanded an average of 11.2 cents per kilometre. The Chinese airlines are clearly competing on lower price with an average charge of 8.8 cents per kilometre. But if we were to compare CX to Air China, the price differential is not that big now at 9.7 cents to 9.2 cents, so the worst may already be behind it.

Operating costs are the key culprit

Where CX has lots of work to do is in cost cutting. If one were to look at operating expense per available seat kilometres flown, CX has got the second highest costs at 8.2 cents (SQ highest at 8.9 cents). Even if we were to exclude the HK$8.5bn fuel hedging loss in 2016, CX’s operating expense per kilometre flown would still be around 7.5 cents. This is lower than the US airlines but still much higher than the Chinese airline’s average operating costs of 6.2 cents.

You might not love it as a consumer…

Granted the Chinese airlines’ lower cost may be due to cheaper labour or landing fees but if CX is to compete against them as well as the budget airlines, they will have to continue to focus on reducing costs.

Unfortunately for the consumer, this means the cheap pastry meals are here to stay and may even be extended beyond the short haul flights. My guess is that CX will increasingly resemble an US airline. There will be more more ancilliary charges, limited inflight entertainment and older planes. Considering that the average fleet age for American, United and Delta is between 10 and 17 years old, beyond the planes currently on order, the average age for CX’s fleet appears likely to rise.

Embed from Getty ImagesFor employees, this is also bad news. Staff costs represents 21% of CX’s revenues and if the company is to try to restore profitability this is the one area that it can control. There is nothing that CX can do about its fuel hedge. Short term capex commitments are also already set. For CX to boost cash flow, it must turn to wages.

…but shareholders may hate it less

The only good news will be to shareholders. After suffering through a 50% correction in share price over the past two years, if CX is successful in restoring its profitability, its valuation gap should narrow with those of its peers.

Embed from Getty ImagesAs a CX frequent flyer, I don’t like the the changes that are coming my way. But as the saying goes, if you can’t beat them, you might as well join them.